Don't Stuck in the Waiting Room!

Register Online Before You Arrive.

We have up-to-date schedules, contact information, and allow you to make appointments online.

What is Prostate Cancer?

Prostate cancer is a significant health issue, ranking second in frequency after lung cancer.

INCIDENCE AND GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION

According to U.S. statistics, one in every seven to eight men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer in their lifetime, but only about one-third will die from the disease. Although statistics in our country are not comprehensive, the incidence rate in and around Izmir has been determined to be 6%. It is a known fact that the incidence of prostate cancer is generally lower in Mediterranean countries compared to Northern Europe. While the incidence rate is also very low in Japan and China, representatives of these races living in North America approach the same risk as a standard white American. In contrast, the incidence of the disease is quite high in the black population.

RISK GROUPS AND NATURAL HISTORY

As mentioned above, some races and geographical regions seem to be at higher risk, but it is well known from autopsy results of men who died from other causes at age 80 or older that every man will develop prostate cancer if he lives long enough. However, one characteristic that may not be seen in any other cancer is that a certain subgroup of prostate cancers are latent, meaning clinically insignificant cancers that allow the patient to live out their life and die from other causes. This situation significantly influences efforts to diagnose and treat prostate cancer, especially in patients of a certain age, as will be discussed later.

It has been speculated that a high-cholesterol diet poses a serious risk for prostate cancer and that the relatively low incidence rates in Mediterranean countries and the yellow race may be related to the use of olive oil and soybean oil. Apart from lifestyle and race, genetic makeup is perhaps the most serious risk factor. Those with close relatives such as a father, uncle, brother, or grandfather with prostate cancer have a 1.5-2 times higher risk, and those with two or more such relatives have a 3-5 times higher risk. If the first individual was diagnosed with cancer before the age of 65, this risk increases even more.

SCREENING OR EARLY DIAGNOSIS?

Given the high incidence and the amount of money spent on its diagnosis and treatment, it may be thought that screening for this disease in the target population is necessary. Screening means examining all individuals over a certain age in a society for that disease. Looking at it this way, it is clear that this would require a huge amount of spending, cause unnecessary anxiety, and identify cancers that do not need to be diagnosed. But more importantly, it should be emphasized that prostate cancer screening is not realistic for Turkey, where more fundamental medical problems (such as infectious diseases, infant and maternal mortality, etc.) have not yet been solved. Therefore, the goal should not be screening but early diagnosis. Different behavior should be exhibited based on risk groups. Individuals with a family history of prostate cancer should start early diagnosis research between the ages of 40-45, while other men should start after the age of 50 and repeat it annually. Men over the age of 50 who visit a urologist for any reason should be evaluated for prostate cancer by the urologist.

SYMPTOMS AND DIAGNOSTIC TOOLS

Prostate cancer, especially in the early stages, rarely causes specific complaints. Urination problems or blood in the urine or semen should not initially suggest prostate cancer. However, it is appropriate for men of a risky age presenting with these complaints to be evaluated for prostate cancer. In the advanced stages of the disease, especially back, lower back, or arm-leg pain may occur, indicating that the bone is also affected.

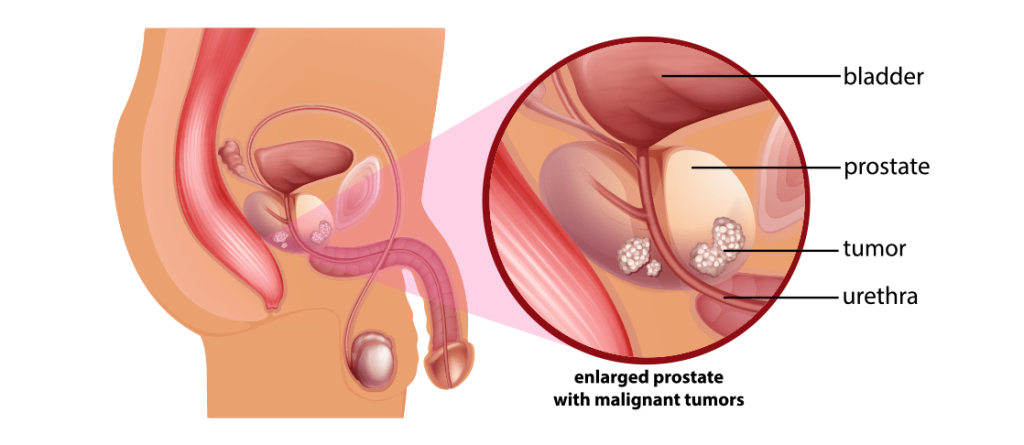

A frequently wondered topic is the relationship between urination complaints and prostate cancer. Essentially, there is no direct relationship between the two. The issue is related to the presence of two different diseases in two different regions of the same prostate at the same time. The first disease is benign prostatic hyperplasia, which is responsible for urination difficulty and develops in the part of the prostate adjacent to the urinary tract (central zone), while the second disease is prostate cancer originating from the outer shell of the prostate (peripheral zone), and these two diseases can coincidentally be present at the same time. The common denominator for both diseases is aging. To understand better, the prostate can be likened to an orange. The urinary tract is a canal passing through the middle of this orange. Benign growth corresponds to the fruit of the orange, compressing the urinary canal passing through the middle as it grows and causing complaints. In contrast, cancer originates from the orange peel, so it cannot cause a negative impact on the central urinary tract, especially in the early stages.

In the absence of typical complaints, a urologist must use some diagnostic tools to make an early diagnosis of prostate cancer in a man over the age of 50, whether or not he has urination difficulty or in a man in his 40s with a family history of prostate cancer. These tools are the PSA test and the digital rectal exam. Both diagnostic tools should present normal data. If one is abnormal, it will result in recommending a prostate biopsy to the patient.

PSA, DIGITAL RECTAL EXAM, AND PROSTATE BIOPSY

PSA is a blood protein secreted by prostate cells; its main function is to liquefy semen. It is found in the blood partly free and partly bound to other molecules. What is actually measured is total PSA, which includes both fractions. The other fractions can be measured if necessary and can contribute to the diagnosis. Since PSA is secreted by the prostate, it can be elevated in any prostate disease (benign enlargement, acute-chronic infection, and cancer). Over the past 10-15 years, PSA has served perhaps as the most important cancer marker in medicine, contributing significantly to the early diagnosis of prostate cancer. Since one of the most important level determinants of PSA is prostate size (volume) and prostate size can increase with age, using a universal upper normal value has been gradually abandoned, and a lower upper value has been used, especially in younger patients. Accordingly, upper limits of 2.5 ng/ml up to age 59 and 3-3.5 ng/ml for the age group 60-69 have replaced the previously used universal upper limit of 4 ng/ml. Some even suggest using an upper limit of 2.5 ng/ml for everyone. The goal is undoubtedly to detect more cancer, but this can only be achieved with more biopsies. Therefore, the physician should evaluate the PSA level based on the patient’s age, other existing life-threatening diseases, and, most importantly, the presence of factors that can elevate PSA (catheter, previous systemic infection, urinary tract infection, sudden obstruction, continuous horseback or bicycle riding habits, etc.) and the finding of the digital rectal exam. If in doubt, the value is repeated. This is a somewhat philosophical evaluation and must be done by a urologist. During check-up programs, some general practitioners or family physicians accepting age-adjusted but under 4 ng/ml PSA levels in young patients as normal can lead to serious negative consequences. Unfortunately, even though some recent studies have shown that prostate cancer can exist at any PSA level, PSA will maintain its place until a better marker is found. In this process, the kinetic behavior of PSA over time in individual patients will perhaps be more important than a single numerical measurement.

Digital rectal exam is the fundamental examination of the urologist and an indispensable part of the early diagnosis program for prostate cancer. A normal PSA level should not result in abandoning the digital rectal exam because there are many patients whose prostate cancer diagnosis is based solely on a finding of asymmetry, irregularity, hardness, or nodule in the digital rectal exam. During the exam, the physician determines both the consistency changes and the prostate volume. Since prostate cancer originates from the outer shell of the prostate, it can be felt in the digital rectal exam. Additionally, whether the palpable hardness, if due to cancer, has extended beyond the anatomical outer boundary of the prostate, the capsule, can also be determined during the exam by an experienced hand, which is very important in treatment selection. However, it should be emphasized that today, many prostate cancer diagnoses are made when the digital rectal exam is completely normal and biopsy is performed due to elevated PSA.

Before explaining prostate biopsy, it should be mentioned that prostate cancer is currently an unfortunate type of cancer concerning current imaging technology. Neither a well-performed computed tomography nor an appropriate magnetic resonance (MR) imaging can definitively diagnose prostate cancer at present. They can only suggest a suspicion, which is not sufficient for planning prostate cancer treatment; a tissue diagnosis is necessary. Tissue diagnosis is made through biopsy. The idea that there might be cancer inside the prostate based on PSA levels and digital rectal exam findings can be likened to thinking there might be bruises in an apple without knowing their exact location. Therefore, the aim is to take samples from as many areas as possible, which will be achieved by directing biopsies to different parts of the organ. The use of transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) during prostate biopsy is entirely for guiding the biopsy needles to different areas of the prostate. This procedure is done outpatient, under antibiotic protection, and preferably any blood thinners should be stopped 5-7 days beforehand. Local anesthesia applied around the prostate during the procedure will greatly reduce pain. Depending on the size of the prostate, tissue is taken from 10-14 different regions of the peripheral zone (the shell of the prostate). Each sample corresponds to a tissue column approximately 10mm long and 1mm wide. Each sample is coded according to its exact location (right-left; upper-middle-lower) and sent for pathology. Antibiotics are continued for at least three more days after the procedure. It is natural to have blood in the urine, semen, and rectum for a while. However, if fever rises to 38 and above, with chills and urinary difficulty, especially on the day of or the day after the procedure, it should be taken seriously and reported to the doctor. This serious infection situation, seen at a rate of 2-3%, may require patients to be monitored in the hospital for a few days.

WHEN NO CANCER IS FOUND IN THE BIOPSY

This is certainly a situation to be happy about from the patient’s perspective, but it must be well analyzed. If no cancer is found in the pathology report, the following scenarios are possible: 1. Findings entirely of benign enlargement 2. In addition, inflammatory tissue findings 3. Along with these, one or more foci of high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN) 4. With any of these, a focus of atypical acinar proliferation (ASAP). The presence of the first two means there are no suspicious findings. However, the chance of a single 10-14 core biopsy accurately revealing what is happening inside the prostate is only about 85-88%. Therefore, especially in young men with familial risk, high PSA levels, suspicious digital rectal exam findings, or a free/total PSA ratio below 10%, it would be appropriate to recommend a second biopsy after a reasonable period considering the remaining 15% risk. In patients other than these, monitoring PSA over time and deciding on a second biopsy if an increase of 0.6-0.7 per year occurs or changes develop in the digital rectal exam findings is a widely used method. Usually, second biopsies evaluate more foci and obtain tissue from regions of the prostate that have not been sampled before (central zone, etc.). Unfortunately, even after a second biopsy, the accuracy is only about 92-93%.

In the presence of the third and fourth scenarios, it means there is a finding in one area of the prostate that could be a precursor to cancer (high-grade PIN) or a very small cancer-suspicious focus that the pathologist had difficulty diagnosing (ASAP), which suggests recommending a second biopsy after 6-12 weeks after re-evaluating the pathology report. Sometimes in such cases, patients ask why the prostate is not immediately removed, like the removal of the uterus in women, to be on the safe side, which will be addressed later when surgery is discussed. What should be said at this point is that no prostate cancer treatment method, including surgery, will be applied unless there is clear cancer evidence. The fear that biopsy might trigger or spread cancer is entirely false and unfounded. It must be remembered that biopsy is the only method to diagnose cancer. Patients diagnosed early can be comfortable for life with appropriate treatment. If things did not go as well as expected, the reason is not the effect of the biopsy but that the diagnosis was made relatively late.

CLARIFICATION OF PROSTATE CANCER DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT SELECTION

The pathology report from the initial or subsequent necessary biopsies may document prostate adenocarcinoma. The report emphasizes the following points: The number and locations of cancer foci, the percentage of cancer in the total length of tissue taken, the cancer ratio in each focus, and the cancer grade (Gleason score), which describes the aggressiveness of the cancer on a scale of 1 to 10. These data give the physician the opportunity to assess very important points such as the tumor volume present inside, the degree of aggressiveness, the risk of having breached the capsule, and the risk of metastasizing to other organs. In addition, some validated tables (nomograms) can be used by entering patient data for this purpose. In necessary cases, bone scanning (scintigraphy) and abdominal scanning (CT-MRI) are performed to determine the presence of distant organ spread, lymph node involvement, or capsule breaching, after which the physician determines the stage of the disease (these tests are not required for every case, they are only used if a high risk of spread is predicted. Despite this, the patient’s preference, in addition to the physician’s, should play a role here. The patient may want to know for sure that all scans have been done and that there is no spread). Accordingly, the disease may have been caught in the early (localized=organ-confined) stage, in the locally advanced stage (breached the capsule but no distant spread), or in the metastatic stage (prostate cancer spread to lymph nodes, bones, lungs, or other organs). Each stage has different treatment options. Additionally, the patient’s age, if any, other important health conditions (heart, diabetes, chronic bronchitis, other cancers, etc.), previous surgeries (previous prostate surgery for benign enlargement or pelvic region surgeries), prostate volume, and urination status also play a role in treatment selection.

TREATMENT OF EARLY-STAGE PROSTATE CANCER

In cancer caught in this stage, the patient has the luxury of choosing one of several treatment methods. Even in well-selected cases of older age, careful monitoring without any treatment may suffice. This situation must be well explained to the patient, as they may find it difficult to understand why the sensitivity shown in diagnosing their cancer is not shown in treating it. Active treatment options include radical prostatectomy, radiotherapy, and brachytherapy. Cryotherapy and high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) are not currently established treatment alternatives.

Radical prostatectomy has been shown to give the best long-term results in early-stage prostate cancer, especially in those with urinary complaints and large prostates, making it the preferred treatment method. It can be performed via open retropubic, open perineal, or laparoscopic/robotic approaches. Regardless of the method used, it is a specialized operation where the knowledge and skills of the person performing it directly affect the patient. The hospital stay is typically 3-4 days, and the patient usually has a catheter for about 8-9 days.

DO YOU NEED HELP?

Request a Callback Today!

We will usually contact you within 24 hours of your request.